Lutheran liturgy is more than just a set of worship practices; it is a rich tradition deeply rooted in the theological convictions of the Reformation. The history of Lutheran liturgy reflects the dynamic interplay between the church’s efforts to maintain the best aspects of the Christian tradition and Martin Luther’s desire to reform liturgical practices that, in his view, had become overly complicated, obscure, and disconnected from the Word of God. Over the centuries, Lutheran liturgy has evolved, but it has always sought to preserve its core theological principles: the centrality of Scripture, the gospel of grace, and the communal nature of Christian worship.

The Early Church and Pre-Reformation Context

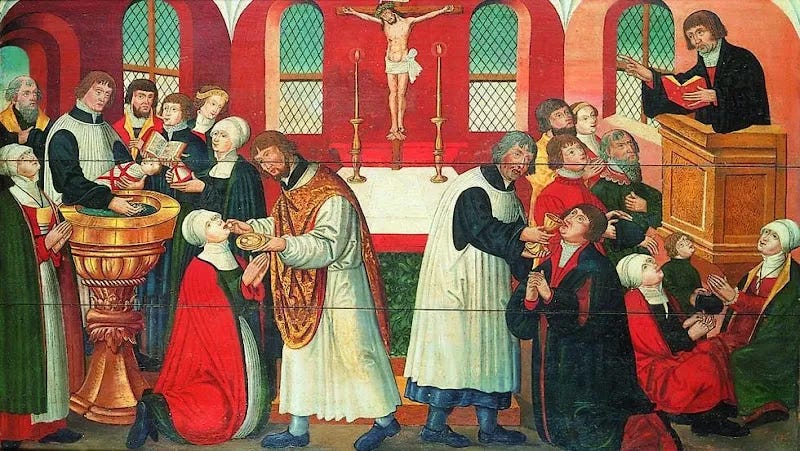

Before we explore the specifics of Lutheran liturgy, it’s helpful to briefly touch on the liturgical traditions that preceded the Reformation. Christianity, from its earliest days, was shaped by liturgical practices that emerged out of the Jewish synagogue traditions and the early Christian communities. By the time of the Middle Ages, the Roman Catholic Church had developed a highly elaborate liturgical system, with Mass being the central act of worship. The liturgy was conducted in Latin, and much of the congregation, though present, had little understanding of the language or the theological meaning behind the rituals. The priesthood was seen as the mediator between God and the people, and the laity had limited participation.

By the time of the 16th century, the Western Church was in need of reform—not only in its doctrine but also in its practices. It was into this context that Martin Luther’s Reformation was born.

Martin Luther’s Reform of Worship

When Martin Luther famously nailed his 95 Theses to the door of the Wittenberg Castle Church in 1517, his goal was not initially to break away from the Roman Catholic Church but to reform it. However, his theological convictions led him to challenge many practices of the Church, including those related to worship. For Luther, the liturgy was not simply a ritual to be performed by the clergy on behalf of the people. Instead, he viewed worship as a communal event where the congregation participated in receiving God’s gifts of Word and sacrament.

Theological Principles Underlying Lutheran Worship

Luther's reforms in liturgy were guided by a few key theological principles:

The Centrality of the Word: Luther believed that Scripture must be the focal point of Christian worship. In contrast to the medieval emphasis on rituals, the Word of God—preached and read—was to be central. The Bible was to be accessible to all believers, not just the clergy. This was why one of Luther’s most radical changes was the translation of the Bible into the vernacular language (German in his case), so that laypeople could read and understand Scripture for themselves.

Justification by Faith: One of Luther’s central doctrines was justification by faith alone (sola fide). The liturgy, especially the celebration of the Eucharist, was to be a means of conveying the gospel—God’s grace to sinners—not a means of earning salvation. The Mass, with its focus on the sacrificial death of Christ, was reformed to emphasize Christ’s completed work of salvation rather than the idea of Christ being repeatedly sacrificed in the Eucharist.

The Priesthood of All Believers: Luther rejected the notion of a clerical caste that mediated between God and the people. Instead, he emphasized that all Christians—whether clergy or laity—are part of the “priesthood of all believers.” This meant that worship was a communal event where all Christians were invited to participate actively.

Liturgical Changes in the Early Lutheran Church

Luther’s reforms affected nearly every aspect of the liturgy. Some of the major changes included:

The Language of Worship: Luther replaced Latin with the vernacular language of the people. The first major liturgical book of the Lutheran Reformation, the Deutsche Messe (German Mass), was published in 1526. It was a simplification of the Roman Mass but retained many of its elements. The sermon, hymns, prayers, and Scripture readings were all in German, which enabled the congregation to understand and actively participate in the service.

The Eucharist: Luther maintained the sacramental nature of the Eucharist but rejected the Roman Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation (the belief that the bread and wine become the literal body and blood of Christ). Instead, Luther affirmed the "real presence" of Christ in the Eucharist, meaning that Christ is truly present in the elements of bread and wine but without the need for a change in substance. The focus of the Eucharist was to be on Christ's gift of grace.

Simplification of Rituals: Luther sought to simplify the liturgy and remove what he considered unnecessary or distracting rituals. He eliminated some of the elaborate medieval ceremonies and focused on the essential elements of worship, such as Scripture reading, preaching, prayer, and the sacraments.

Hymnody: One of Luther’s most lasting contributions to liturgy was his emphasis on congregational singing. He wrote hymns that were accessible to the average person, encouraging the laity to participate in worship through song. His famous hymn “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God” became an anthem of the Reformation and has remained a staple of Lutheran worship to this day.

The Development of Lutheran Liturgy in the Post-Reformation Era

While Luther’s reforms were foundational, the development of Lutheran liturgy continued after his death. The Formula of Concord (1577), one of the key confessional documents of the Lutheran Church, continued to shape Lutheran worship practices. Different regions and Lutheran traditions, particularly in Germany and Scandinavia, began to develop their own liturgical variations, but they remained centered on the core principles that Luther had established.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, many Lutheran churches began to reintroduce more elaborate elements into their worship, reflecting a broader trend in Protestantism toward a more formalized liturgical style. Despite this, the emphasis on Scripture, the sermon, and the sacraments remained intact.

The 20th and 21st Century: Renewal and Reaffirmation

The 20th century saw a renewed interest in liturgical reform within the Lutheran Church. In particular, there was a desire to return to a more ancient and historically grounded form of liturgy that would express the timeless truths of the Christian faith. In many ways, the liturgical changes of the mid-20th century (such as the introduction of the Lutheran Book of Worship in 1978 in the U.S.) were an attempt to strike a balance between historical continuity and contemporary relevance.

At the same time, Lutheran worship remained firmly rooted in its Reformation heritage, continuing to emphasize the Word of God, the sacraments, and the priesthood of all believers.

Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy of Lutheran Liturgy

The history of Lutheran liturgy is a story of theological conviction, reform, and renewal. From Luther’s radical break with medieval practices to the liturgical practices of the contemporary Lutheran Church, the central themes have remained constant: a focus on Scripture, the gospel of grace, and the full participation of the congregation in worship. As Lutheran liturgy continues to evolve, it retains its historical and theological integrity, offering believers a way to worship God in spirit and truth while remaining firmly anchored in the riches of the Reformation.